Newsletters, magazines, coffee table books and reports

An excerpt from the Editor’s note:

Dear readers,

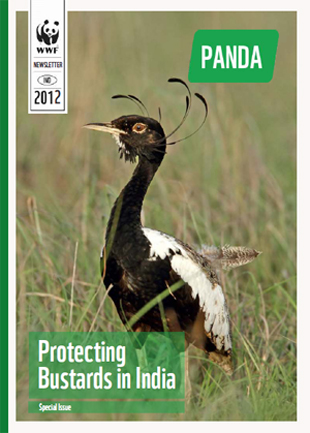

I remember reading about the Great Indian Bustard in a grade-school textbook – and never after.

Since then, the Great Indian Bustard has persevered in my mind (and possibly, in yours too) as the exemplar of endangered species on the verge of extinction. And so, to most people, this is what the Bustard has remained – a textbook example of a species tottering on the brink of extinction.

It is now time to draw the Bustard out of the textbook, and into context. In the Introduction to this special issue, Dr. Asad R. Rahmani asks a precarious question – “Can we prevent the extinction of Indian Bustards?” Heading the checklist of solutions he provides, is the need to reorient ourselves towards conservation itself– to expand our idea of vicinity to include not only that which affects us, but also that which we affect.

A coffee table book for Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), in association with the National Health Agency (NHA), covering 100 interviews and stories of rural beneficiaries of ‘Modicare’ from ten states across the country.

An excerpt

Doctors fixed the hole in her heart – and she stole theirs.

A wide, toothy mouth and beaming black eyes smile up at you from Kajalnetra’s face. She has been well-named – her beautiful eyes do look like they are naturally rimmed with kohl. A year ago, when Kajalnetra was three, a doctor and nurse visited their home on a routine visit for free checkups under the Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana (RSBY) scheme. When they listened to the little girl’s chest, they found an unusual murmur in her heart and recommended an ECG. Kajalnetra’s parents nervously took her to the medical college close by, where, an ECG later, doctors confirmed that she was suffering from congenital heart disease and required surgery.

For Papitha and Kishore, Kajalnetra’s parents, the diagnosis both explained her mysterious fevers and caused them further worry. How would they afford treatment for their eldest child? Kishore was a mechanic, earning about Rs. 300/- a day when he finds work, and Papitha was a housewife. In their joint family of Kishore’s parents, brother and his wife and their two children, Kishore and his family of five (Kajalnetra has two younger siblings), the total family income amounted to only about Rs. 6,000/- a month, barely enough to take care of their needs. They had the rest of the family to think of too. They took comfort in the fact that one of their neighbours – Sunitha – had been diagnosed with the same condition when she was a child – and was now a young woman of twenty four. Perhaps God would take care of Kajalnetra in the same way?

The family made their peace with Kajalnetra’s condition this way – until one day in September when another visiting doctor told them that they were eligible for free surgery under the Prime Minister’s Jan Arogya Yojna scheme! The family wasted no further time and took the four year old to Bilroth Hospital, Chennai, 120 kilomteres away and her Kajalnetra’s surgery was scheduled for 25th October 2018. During the next four days at the hospital, the little girl was a model patient, taking medicines well, listening to instructions and stealing her doctors’ hearts.

Now, Kajal, as her parents affectionately call her, is back home to her ABCs and chasing her little sister around the house with a little toy gun. Ask her what she wants to be when she grows up, and she points her tiny pistol at you and exclaims, “Police!”

An excerpt:

One hundred interdigitated teeth glinted in the moonlight.

It was the year 2009 and the cold of winter had set in. Hundreds of villagers, the entire police department, the forest department and anyone with a smidgen of curiosity had gathered on the banks of the Ganges at Hastinapur, Uttar Pradesh to witness what was to be one of the key stages of the Gharial Reintroduction Programme – the release of captive-bred gharial into the Ganges.

One hundred teeth that sit atop the food chain – and yet these jaws have never had a Hollywood blockbuster made about them. They should have though, I would have thought – gharial are fascinating enough. Like the more celebrated (but rather maligned) great white shark, in truth, the gharial has plenty to be proud of – as an indicator species, it testifies to the health of the river ecosystem it occupies, it is the only surviving descendant of the Gavialidae family of crocodilians, and finally, as a piscivore, it is harmless to humans.

An excerpt from the foreword

You probably spent the better part of your childhood on the playground – the swings taught you gravity; the slides taught you patience while you awaited your turn; you learned to share responsibility while spinning the merry-go-round.

We learn where we play.

Now imagine a playground where the toys are used syringes, the slide is just a large pile of garbage and worst of all – no one will come looking for you when it gets dark. For a lot of children in India, this is a harsh and unfortunate reality.

We’re working to change this – all children deserve a safe nest away from the threats of homelessness, substance abuse, disease and illiteracy, where they can grow to face the world. And who better to provide such a learning eld than a group of motivated mothers?

In 2018-19, we brought together, imparted training to, and equipped women to be such nest-builders who could encourage and promote a healthy and safe environment for children onthe streets to grow up in. The future now looks brighter not only for the children that have benefitted, but also the women who stepped up to take on these roles, earning them both income and independence.

An excerpt from the Editor’s note:

Dear readers,

Just as fascinating as the image on the cover of this issue’s Panda, is the story of how we came to acquire it.

If the legend of the mahseer’s Indo-Persian etymology is to be believed, then this is truly the tiger (“sher”) among fish (“mahi” ). And yet, when it comes to how well it is photographed, – or for that matter, studied – the mahseer stands nowhere close to the tiger.

It was beginning to seem like a photograph that truly captured the essence of this great fish did not exist. In all the images we had, the mahseer did not exist on its own; in all the images we had, the mahseer was a prize. And if there was no “life” in the photo, as our designer said disappointedly, it was because, in each, the mahseer was dead.

If this editorial seems only to bemoan the lack of photographs of a species, it is because it is precisely this that makes its conservation ever more difficult. If we can still draw a parallel between the tiger and the mahseer, it is that the two may be ultimately saved by the attention they receive (or are due to receive) not only in conservation circles, but also in circles without. Local communities, anglers and fly-fishers are such groups that must be encouraged in conservation. If it is just the photograph that anglers are after, then catch-and-release schemes bode well for the mahseer – the angler gets his photograph and the fish is free to live.